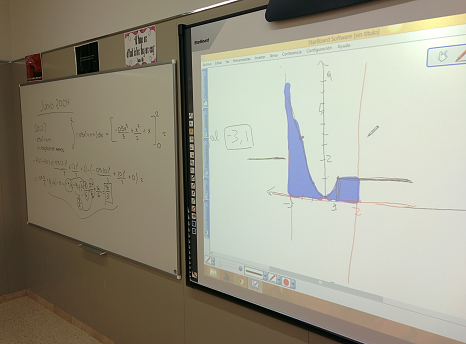

We are increasingly getting used to see our kids having access to a whole set of sophisticated (and expensive) tools designed to helping them study: laptops, next generation tablets and mobiles, digital blackboards, very advanced and complicated software, internet and so on. Nevertheless, I believe that the most important thing still is, and will always be, a passionate teacher and the will to learn of the students. You can encourage learning without any of these gadgets, and you can be very effective in breeding knowledge and attitudes with a pencil, somewhere to write on and a bit of creativity.

Two years ago I went to Nicaragua with an education Spanish charity and I had, among other goals, the objective of working with the local teachers in maths pedagogy. Specifically we had to work about fractions equivalency and operations, and we had to bear in mind not just the national curriculum but also the difficult conditions they face every day, almost without material means or support of any kind. That's the main reason the charity worked there. Because of the students' age, which was rather diverse, from may be 6 to young teenagers of even 15 -this is only one of the difficulties these teachers have to deal with, if you believe your job is tricky you should go there and see how they manage to teach in these conditions. Well, I wanted to focus it as a game, and one with different levels. After some weeks of thinking and reading about the question that's the game I proposed for learning fractions equivalency:

You need something to write with (say a pencil) and something to write on (say a paper). You don't need anything else. Not even a blackboard and not for sure a maths book, which they did not have most of the time. Then you make cards, or better, the kids make their own cards, and in these cards you (they) write fractions in different forms: 1/2, 2/2; 1/4, 2/4, 3/4, 4/4.... for the whole game you write percents: 25%, 50%..... numbers: 0,33; 0,4; 0,5; 0,66; 0,75....... and there is no rule saying you need to stop in 1, you can make fractions above the unit: 6/4; 12/6; 20/5........ and percents and numbers as well: 150%; 300%; 1,25; 2,5; 4............ and even mixed numbers: 2 1/4; 1 1/5....... The amount of cards you'll have at the end is up to you. It depends on the number of kids you are working with, the deepness you need to work and so forth. I like to have many, hundreds of them. You can also repeat them, make some sets, which will help you to work in groups.

And what can you do with these cards? Everything.

I proposed them 4 or 5 different games, but they could (and ought to) work out their own games with them: the more the kids played, the more used they'd get to the fractions equivalency, and the equivalency between fractions, real numbers and percents, and operations with fractions like adding and substracting. My idea was the kids working in groups -because they improve their social skills- but you can also do it individually if you believe that fits better with your conditions. Some of my proposals were: Giving a whole set of cards to each group and a) classify the fractions that are actually the same (like 2/4; 1/2; 5/10) -fractions equivalency-; b) find a number by adding fractions: (find 2? one group find it by adding 1/2 + 4/4 + 2/4 another group can use another cards 4/3 + 2/3...); c) and d) You can repeat these games with fractions and percents and numbers all together and so one can find 2 by adding 0,5 + 100% + 50/100, for instance. And in the game c they'll have a little mountain where 6/3, 4/2, 200%, 50/25 and the number 2 will be together representing the same amount. Another little mountain with 1/3; 0,33; 33%; 3/9, 2/6..... Nice, isn't it? The more they play, the better they'll understand what fractions actually mean. A second session of games, once they are used to the cards (which may as well be in the third or fourth lesson or later, depending of their rhythm) would be giving them an incomplete set of cards, and every group a different one. So, now you can create two new kind of games: 1) negotiation games, where to get to the result they'll need to negotiate with other groups to get the cards they need, while offering the cards they don't need. Interesting introduction to trade, bargain and so on -there is a sort of introduction to

David Ricardo and trade theory here, eh?- and working a lot of social skills. 2) You can introduce substracting (and even other operations) to arrive to the goal number.

As a matter of fact you could make up many more games with these cards, focusing on different needs (discover the hidden card -intro to equations-; games to identify prime numbers, and so on). They'll pick it up very quickly, though, and the main target of the cards, let them get the hang of the fractions, will be achieved in just one or two sessions. Besides, they have made the game themselves, and they have learned all this while having fun, challenging their minds. You don't need more than your will and a pencil.

I guess most of you have got it straight away, but I'm going to explain it with a bit more of detail just in case anyone studied laws -sorry, solicitor and lawyer friends, I know the truth can be painful. First, the mnemonic rules: You all know multiplying by five is easy, just the half ten (v.gr. 8x5 = [the half ten of 8] 40). Most of you might also know that multiplying by nine is very easy indeed, just the previous ten and what's missing to get to nine. It is to say: if you want to multiply, for instance, 6x9, you take the previous ten of six (5, fifty-something), and the unit is what's missing to make nine: 4. So, 6x9= 54. This works. Ok, we've got every single number multiplied by 5 or 9. Then, adding up to four times can be done mentally without effort. So, we have deduced every single digit multiplied by 1 to 5 and by 9. Now we have these two ops, 6x6=36 and 7x8=56, which we'd better memorize (we could eventually add them but I have realized it's a bit tricky for children) and now we have a supporting point to get to every single-digit multiplication directly or by just adding or substracting the number once. Think about any single-digit multiplication, let's say 6x7? the child mental process would go: Ok, I know 6x6=36, so if I add 6 I'll have 6x7! 36+6=42. Good. 8x3? Ok, eight and eight, sixteen, and eight twenty-four. Easy. 8x6? Humpf, well I know 8x7=56, so if I substract 8 I'll have 8x6 -> 56-8=48. Or either I know 6x6=36 I add six twice and I'll have 8x6 -> 36+6=42 +6= 48. And so on, and so forth.

I guess most of you have got it straight away, but I'm going to explain it with a bit more of detail just in case anyone studied laws -sorry, solicitor and lawyer friends, I know the truth can be painful. First, the mnemonic rules: You all know multiplying by five is easy, just the half ten (v.gr. 8x5 = [the half ten of 8] 40). Most of you might also know that multiplying by nine is very easy indeed, just the previous ten and what's missing to get to nine. It is to say: if you want to multiply, for instance, 6x9, you take the previous ten of six (5, fifty-something), and the unit is what's missing to make nine: 4. So, 6x9= 54. This works. Ok, we've got every single number multiplied by 5 or 9. Then, adding up to four times can be done mentally without effort. So, we have deduced every single digit multiplied by 1 to 5 and by 9. Now we have these two ops, 6x6=36 and 7x8=56, which we'd better memorize (we could eventually add them but I have realized it's a bit tricky for children) and now we have a supporting point to get to every single-digit multiplication directly or by just adding or substracting the number once. Think about any single-digit multiplication, let's say 6x7? the child mental process would go: Ok, I know 6x6=36, so if I add 6 I'll have 6x7! 36+6=42. Good. 8x3? Ok, eight and eight, sixteen, and eight twenty-four. Easy. 8x6? Humpf, well I know 8x7=56, so if I substract 8 I'll have 8x6 -> 56-8=48. Or either I know 6x6=36 I add six twice and I'll have 8x6 -> 36+6=42 +6= 48. And so on, and so forth.