Economics

It's a battle of the ideas. Watch. Read. Be critical. Argue. Figure things out.

Teaching

It's more important to teach how to think than what to think.

Cooperació internacional

Des de la solidaritat, l'estima i el respecte entre els pobles i les persones.

Technology teaches

Tech tools that help us teach... and learn.

Londres no és Itaca

Però ha d'estar en el camí.

dimarts, 4 de juny del 2013

explicar l'esperança de vida / Explicar la esperanza de vida.

dimarts, 28 de maig del 2013

When GDP is not a good indicator (and why)

This year our outcome is just 2 chickens... I eat them both. None for you. GDP will say we have 1 chicken per capita. goo.gl/lz9EA

— Kepa G. de Latorre (@KepaGdeLatorre) 30 de maig de 2013

GDP is widely used as an indicator of development. As a matter of fact it is the main indicator mass media, economists and politicians use to show how an economy is performing, and we rarely see other figures. However, GDP is not always a good indicator, taken alone. In this post I intend to demonstrate why not. I can advance that we'll find two issues: average and market dependence.

As it does not exist a market for the environmental value of conserving the forest it has no room in the GDP... goo.gl/lz9EA

— Kepa G. de Latorre (@KepaGdeLatorre) 30 de maig de 2013

dimecres, 17 d’abril del 2013

Manual de guerrilla para sobrevivir a los modales ingleses

Pero no te dejes engañar: son corteses, pero son humanos, así que han desarrollado estrategias, matices imperceptibles en la entonación, gestos sutiles, que les permiten ser extremadamente bordes cuando el cuerpo se lo pide, eso sí, manteniendo la compostura y flema británicas. He descubierto que el inglés es el único idioma del mundo (hasta donde llega mi, por otro lado escaso, bagaje lingüístico-cultural) donde "Thank You" puede querer decir "eres tonto" y "I am sorry" puede perfectamente significar "que te follen, zorra". Sería algo así: "I have told you the black one. Thank You." Profundicemos en el detalle, porque el texto llano y escrito no refleja fielmente todo el proceso: Se debe hacer enfatizando y ralentizando la entonación en "the black", para que se note que el otro es medio lelo y no había entendido a la primera, y escupiendo el thank-you lentamente y desde el paladar, levantando ligera -pero perceptiblemente- el labio superior y pegando dos pequeños y firmes cabezazos afirmativos al final de la frase, uno por sílaba. El labio superior se deja arriba el tiempo que consideremos necesario, hasta que el lenguaje no verbal del interlocutor nos diga que definitivamente ha entendido el insulto. El susodicho nos puede contestar entonces: "I know, madam/sir, though I have no black ones left, I am sorry." En este caso conviene acentuar también el I am sorry y ladear ligeramente la cabeza, alejando la barbilla, hasta mirar al contrincante -verbal- desde un solo ojo, e incluso arquear las cejas y apretar los labios mientras se levanta una -y solo una- de las comisuras de los labios (yo recomiendo la más alejada). Si se siente uno inspirado puede incluso finalizar el escorzo encogiéndose de hombros. La conversación, pues, se podría traducir por: "que te he dicho que el negro, mongol". "No quedan, te jodes.".

divendres, 5 d’abril del 2013

Fer que els Mercats funcionen per als Pobres (M4P)

dilluns, 18 de febrer del 2013

It's the governance, stupid!

|

| The oxymoron of capitalist democracy |

|

| The ECB President and the Spanish Economy Minister having fun |

dimarts, 12 de febrer del 2013

És la governació, estúpid!

|

| El president del BCE, Mario Draghi, i el ministre d'economia espanyol De Guindos fent unes rises |

Es la gobernanza, estúpido!

|

| El presidente del BCE y el ministro de economía español divirtiéndose |

dijous, 31 de gener del 2013

Teaching Pills 4 - Applied Financial Maths: the implicit grant of the ICO student loan

I have only exposed the differential figures between option A and option B and C, which was the relevant information to make a decision in this case. Thereby year t is the year you start to pay the loan and not the year you received it, which would be the proper "year zero" to know the total amount of the implicit grant. It is indeed interesting to calculate the global gaining of the loan -to know which percent of it is a sort of implicit transfer- and if you feel curious, given a 2% inflation rate it would be roughly a 19-23% depending on the payment option you choose, and in our study case it would represent an implicit grant of 3.000€ to 3.800€, but we can't infere the actual inflation rate and such long term predictions are rather unreliable. We know, however, that given any positive inflation we'll have this implicit grant and that the higher inflation the higher grant. Now we just need to patiently wait until 2023 to check which the actual grant will have been***.

*deflation is a real danger, though, if the crisis carries on for very long, Germany is still sickly obsessed with inflation and/or more bubbles burst, but this is another point (macroeconomics and economy policy issues) and one of the reasons I DON'T give any advice.

*** And I found a way of writing a future perfect somewhere ;)

diumenge, 20 de gener del 2013

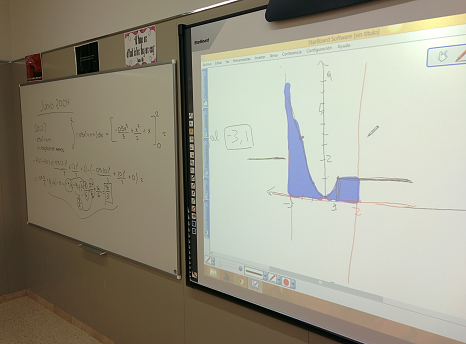

Teaching Pills 3: teaching through ICT

In my last TP post I wrote about how you can teach with almost no material resources and in this one I'd like to show just the opposite, how you can use in a sensible way some of the huge amount of resources currently provided by the ICT. There are many websites, blogs and even apps which may help you to prepare materials, to decide teaching strategies and to support your work. The few times I have had the chance to teach myself I have relied heavily on powerpoints, dynamic graphs and maps. I have also made internet research about the subject (no matter I had it very clear in my mind), keeping an open-minded approach not only because I am a novice (which I clearly am) but because you may find extraordinary tools. Today I'm speaking just about two sites I've already used. However, before starting I'd better say two important things: firstly, these resources are a support to your lessons, but they can't substitute the teacher, it's important that you prepare yourself properly for every lesson and that you don't rely too much on your PPT or your internet connection. Questions will be asked and you ought to be ready to clearly explain them. Secondly, it's important that you adapt the resources you find to your objectives and to the stages you are working with, because a messy explanation may be worse than no explanation. Once these two warnings have been issued, let's go to the resources:

http://www.gapminder.org/downloads/life-expectancy-ppt

Worldmapper.org: Put your stats on a map

|

| This is a demographic-corrected UK map |

Of course, this two are samples I knew about because I had used them before to teach. You could also explain the carbon footprint and let the kids calculate their own one; there is plenty of sites with Maths or English games... it's up to you to use these resources and make learning a bit funnier.